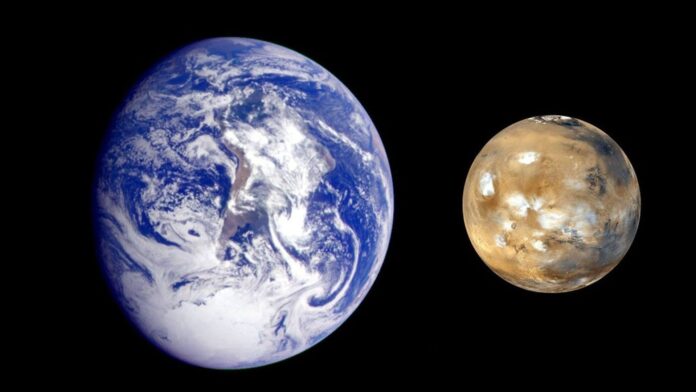

New research reveals that Mars plays a surprisingly critical role in regulating Earth’s long-term climate, influencing cycles that span hundreds of thousands to millions of years. While Venus and Jupiter dominate Earth’s orbital dynamics, simulations show that removing Mars from the solar system disrupts key climate patterns. This discovery reframes our understanding of planetary stability, suggesting that the presence of a stabilizing outer planet—like Mars—may be more common than previously assumed, potentially increasing the odds of finding habitable exoplanets elsewhere in the galaxy.

The Unexpected Role of Mars

For decades, scientists have understood that Earth’s climate is shaped by Milankovitch cycles—long-term variations in Earth’s orbit and tilt driven by the gravitational pull of other planets. Venus and Jupiter exert the strongest influence, but the effect of Mars was thought to be minimal. Recent simulations led by Stephen Kane of the University of California, Riverside, challenge this assumption.

The team ran detailed models of the solar system, systematically testing the effects of each planet on Earth’s orbit and axial tilt. The results were striking: removing Mars from the simulation eliminated two crucial Milankovitch cycles with periods of 100,000 and 2.4 million years.

“When you remove Mars, those cycles vanish,” Kane stated. “And if you increase the mass of Mars, they get shorter and shorter because Mars is having a bigger effect.”

This suggests that Mars “punches above its weight,” exerting a disproportionately large influence on Earth’s climate stability.

How Mars Stabilizes Earth’s Tilt

Earth’s axial tilt, or obliquity, varies between 21.5 and 24.5 degrees every 41,000 years, impacting seasonal intensity and long-term climate patterns. While the moon has long been considered the primary stabilizer of Earth’s tilt, the simulations demonstrate that Mars’ gravity also contributes significantly. Increasing Mars’ mass in the simulations further stabilized Earth’s tilt, suggesting that a larger outer planet could enhance orbital stability.

This finding is significant because it potentially lowers the bar for habitable exoplanets. A planet doesn’t necessarily need a large moon to maintain a stable tilt—a modestly sized outer planet like Mars may suffice. This widens the search criteria for Earth-like planets beyond our solar system.

Milankovitch Cycles and Long-Term Climate

The Milankovitch cycles control variations in Earth’s axial tilt, orbital eccentricity (how elliptical the orbit is), and the precession of the equinoxes. These cycles trigger ice ages and warm periods over geological timescales.

The 430,000-year cycle, driven by Venus and Jupiter, remains unaffected by Mars’ presence. However, the other two cycles—those that vanish when Mars is removed—are critical for long-term climate regulation.

It’s important to note that these cycles operate over millennia and are unrelated to the current, human-caused climate change. Milankovitch cycles shape Earth’s climate over geological timescales, ensuring that ice ages don’t last indefinitely.

Implications for Exoplanet Research

The discovery that Mars stabilizes Earth’s climate has implications for the search for habitable exoplanets. Astronomers should now consider the presence of a stabilizing outer planet as a key factor when assessing planetary systems.

“When I look at other planetary systems and find an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone, the planets further out in the system could have an effect on that Earth-like planet’s climate,” Kane explained.

The existence of Mars raises questions about what Earth’s climate would be like without it, and whether complex life could have evolved under such conditions.

Ultimately, this research highlights the interconnectedness of planetary systems and underscores the importance of considering gravitational interactions when evaluating the habitability of exoplanets.